2000

2000 Works

Media attention to Arkley was unprecedented in 2000, with stories ranging from serious reviews to fevered speculation on escalating prices for his works at auction, and even hints of the development of an ‘Arkley school’.[1]

Media attention to Arkley was unprecedented in 2000, with stories ranging from serious reviews to fevered speculation on escalating prices for his works at auction, and even hints of the development of an ‘Arkley school’.[1]

There was still uncertainty about how to gauge his overall achievement, so soon after his death. In January, in a Herald Sun story speculating on which Australian artists might still be seen as significant twenty years later, NGV director Gerard Vaughan was quoted as predicting that Arkley’s reputation could only increase over time.[2] Others, though, like the Herald Sun’s art critic, Jeff Makin, were more negative, at least initially – although Makin’s approach softened during the year, as Arkley auction prices climbed steadily.[3]

Arkley’s Venice exhibition was re-staged at the Ian Potter Gallery at the University of Melbourne, in January (later travelling to Queensland). Those who had been unable to visit the Biennale appreciated the opportunity, but critic Peter Timms was strenuously unimpressed, complaining that Fabricated Rooms demonstrates ‘no understanding of scale’, and accusing Arkley’s friends and supporters of ‘zealously working on his cult’ since his death (Age, 26 January). These barbed remarks – reprinted in 2002 as an exemplar of Australian art criticism since 1950 – were countered in a vigorous response by Stephen Feneley (also an eloquent analysis of Arkley’s late style).[4] In the Herald Sun (31 January), Jeff Makin reiterated a number of Timms’ criticisms.

In February, ABC TV screened ‘Howard’s Way’, a playful account of Arkley’s art by film-maker Tony Wyzenbeek, incorporating substantial footage of the artist speaking illuminatingly about his own work. The documentary, obviously modified after Arkley’s unexpected death, includes interviews with several of the artist’s peers, assessing his achievement. The program used digital techniques to locate Arkley and others ‘in’ his suburban settings, in a witty variant of his own taste for such effects (for this issue, see Carnival 14 and Fig.1.4).

Running parallel to the critical reassessment of Arkley’s art following his death (a process that continues, of course) was the volatile art market equivalent. During the year, Arkley’s work became the increasing focus of market activity, with a series of major sales and auctions. As reporter Ben Holgate observed, in an Age article published in September (unambiguously head-lined ‘Death adds new life to the market’), 1999 had seen the deaths of five major Australian artists, of whom Arkley was easily the youngest – the others being Arthur Boyd, John Brack, Rosalie Gascoigne and Albert Tucker. Holgate’s article discussed the impact on the prices of their works, noting that ‘Arkley’s market legacy has been the most dramatic’, with buyers’ attention falling particularly on suburban images.[5] During 2000, a number of very minor Arkley work-on-paper houses fetched surprisingly high prices, and several paintings with rather vague provenance details also appeared on the market.

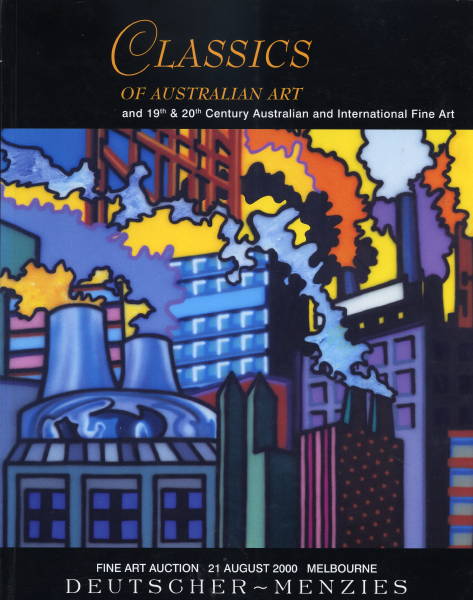

In February, South Yarra dealer Robert Gould, who had known Arkley for some years, and had assembled a collection of his paintings, held a commercial exhibition devoted to works by or attributed to him, almost all of which sold immediately.[6] A series of high profile Arkley auction sales followed. At Deutscher-Menzies (3-4 May), Dining in a Glow 1993 set a new Arkley record, with several other canvases and works on paper also selling for solid prices at both Deutscher-Menzies and Sotheby’s (also in May). Then, in August, a new crop of Arkleys surfaced at auction, with Shadow Factories 1989 fetching just over $365,000 (a new record, which stood until 2007). Arkley’s Baroque Cello (1999) [3/M] also featured in a charity auction (28 Aug.2000) arranged before his death.

Finally, in November 2000, Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Deutscher-Menzies all held Melbourne auctions at which further Arkleys were offered. The most significant, the monumental late masterpiece A Large House with Fence (1998) – mentioned in the press as a possible purchase for the Tate Gallery in London[7] – appeared at Sotheby’s, where it was estimated to sell at somewhere between $300,000 and $500,00, but the work was passed in. Surveying the year’s auction activity in December, Jeff Makin commented that the Sotheby’s auction may have marked a turning-point in the year’s prices, both for Arkley and generally.[8]

Subsequent commentators have suggested that the spike in Arkley prices after his death, followed by a natural correction, exemplified the larger patterns of the market at the time; and his work has also been identified as central to ‘ramping’ and other forms of market manipulation allegedly widespread at the time.[9] While accepting the force of such claims, some common-sense and discrimination needs to be applied to these issues. Arkley prices did head upwards rapidly during 1999-2000, but the major examples auctioned at the time – including the record-breaking Shadow Factories canvas sold at Deutscher-Menzies in August, and A Large House with Fence, both important, mature paintings – should be distinguished from the lesser, often undocumented works that also rose to the surface.

Early in October, writing in the Herald Sun on the Melbourne Art Fair (ACAF7) – where Kalli Rolfe offered the large double-sided drawing Arkley had made in 1999 of Nick Cave[10] – Alison Barclay coined the term ‘the Arkley Effect’, to describe the current buzz of market anticipation surrounding Australian art, quoting ACAF7 director Bronwyn Johnson on the impact of Arkley’s Venice show (along with the rising profile of photographer Tracey Moffatt). Barclay’s comment raises the further interesting possibility that the rapid escalation in prices for Arkley’s works after his death actually had a beneficial impact on the Australian art market, possibly delaying a local variant of the wider overall downward trend.[11]

***

During the year, Arkley houses featured regularly in curated shows. The Queensland Art Gallery included Stucco Home (1991) in ‘Terra Cognita’, a group show embracing suburbia within the larger image of the Australian landscape.[12] House and Garden Western Suburbs, Melbourne 1988 (National Gallery of Australia collection) was included in the large ‘Federation’ show launched at the NGA in Dec.2000, later touring throughout Australia during 2001 and 2002; the painting featured in the substantial catalogue accompanying the show, curated by John McDonald. He included the work as an obvious symbol of the suburban theme in Australian history and culture, about which he wrote acerbically enough, in the ‘Cities and Suburbs’ section of the catalogue: ‘While most recent commentators will allow that there is a kind of poetry in the Australian suburbs, it is hardly a pinnacle of national achievement’, adding that suburbia was most notable now as ‘our most fertile source of comedy’![13]

Despite the plethora of press stories (mentioned above), other substantial 2000 publications on Arkley were relatively scarce. Art & Australia published an obituary by Ashley Crawford, and the autumn issue of the University of Melbourne’s Postgraduate Review included an affectionate memoir of Arkley as a life drawing teacher back in the late 1980s, by Emmaline Bexley.[14] In the Summer 2000/2001 issue of Eyeline magazine, I urged reconsideration of aspects of Arkley’s work, in the light of the extensive studio collections of source material left behind after his death.[15]

2000 Exhibitions

‘Howard Arkley: the Home Show’, Ian Potter Museum, University of Melbourne, 20 Jan.-27 Feb. 2000; and then at University Art Museum, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, 11 March-23 April 2000 [as for Venice 1999; for reviews and reports on the Melbourne exhibition, see 2000 biblio., under Timms, Feneley, Makin; for the Brisbane show, see Anon.: ‘Ten Things’, Rave magazine (Brisbane), 3 July 2007]

‘Howard Arkley’, Gould Galleries, Melbourne, Feb.- March 2000 [see linked entry for details]

Ardoch Youth Foundation exhibition, Gallery Irascible, 423 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy, 17-31 August 2000 [ref. ‘Brushing up for the kids’, Herald Sun, 29/7/00]

- {unknown work, donated}

‘Terra Cognita: the Land in Australian Art’, Queensland Art Gallery Brisbane, 76 Sept.-29 Oct.2000 (curated by Julie Ewington)

7th Biennial Melbourne Art Fair, 4-8 Oct.2000 (for reports, see Barclay 2000, Backhouse 2000)

- Study for Nick Cave (double sided drawing) (1999) [W/P], offered for sale through Kalli Rolfe

- several works offered by Gould Galleries (details unknown; for review, see Makin, Herald Sun, 6 Oct.2000)

- Model Tudor Village, Fitzroy Gardens 1986: Dick Bett Gallery stall (refer Menzies June 2010 auction entry for this work)

‘Federation: Australian Art & Society 1901-2001’, NGA touring exh., 8 Dec.2000-7 July 2002

‘The Persistence of Pop’, Wangaratta Exhibitions Gallery, 19 Aug.-17 Sept.2000

[as for Monash University Feb.-April 1999: see under 1999]

[1] For Arkley followers, see Merz 2000; cf. ‘Critic’s Choice: Erhan Mustafa’, Herald Sun, 13 Dec.1999.

[2] Alison Barclay, ‘2020 Visionaries’, Herald Sun, 8 Jan.2000.

[3] This shift was signalled even by the headlines of Makin’s reviews: a January piece was called ‘House of Horrors’; but by August Arkley’s works had become ‘A Mirror on Modern Life’ (see bibliography for details of Makin’s reviews of Arkley during 2000). Though a traditional landscape painter himself, Makin praised Arkley’s early non-figurative works (see biblio.: 1973, 1975, 1976, 1979 and 1981), but appears to have lost sympathy with the artist’s later development, evidently finding less to enjoy in Arkley’s suburban project than other critics and curators, notably Robert Rooney and Juliana Engberg.

[4] See Timms 2000 and Feneley 2000; Timms’ review is reprinted in Genocchio 2002.

[5] Ben Holgate, Australian, 8 Sept.2000

[6] See ‘Arkley sells’, Age, 16/2/00

[7] Megan Backhouse, Age, 6 Sept.2000

[8] Herald Sun, 18/12/00; of course various factors explain the flattening of art prices generally late in 2000 and into 2001. For example, as Geoff Maslen pointed out in the Age on 11 Nov.2000 (‘Final art auctions start under a cloud’), the international operations of both Sotheby’s and Christie’s were under a legal cloud at the time; for the downturn in the local market, see also Maslen in the Age, 2 Dec.2000 (mentioning Arkley specifically).

[9] For discussions of these issues at the time, see e.g. Safe & Holgate (2001), Leyden (2001), and Hutak (2001); see also, more recently, Wilson-Anastasios (2008)

[10] During 2000, Alison Burton transferred control of the Arkley Estate from Tolarno to Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art (where Juan Davila had also recently transferred).

[11] See Michael Reid, as quoted in Sexton & Safe, Australian, 29 Nov.2000.

[12] For the curator’s comments, see Ewington 2000

[13] McDonald 2000, p.73; Arkley’s painting is reproduced on p.100. One awaits with some misgivings the future volume of McDonald’s large-scale survey of Australian art (2009ff.) dealing with Arkley and his period.

[14] Bexley 2000; cf. Crawford 2000

[15] Gregory 2000; this article formed the basis for my extended comments, based on much more detailed research into Arkley’s archive, in Carnival (2006).